If the constitutionality of the Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act (Act 70 of 1970) was challenged in the Constitutional Court it would likely lead to the repeal of the subdivision restriction on farmland. This would make small farms much more affordable in South Africa. It would also drive large-scale land reform through the free market as land is inexpensive in South Africa. These cheap land prices are currently only available to wealthy South Africans who can purchase large farms. Small and medium-sized farmers are paying artificially higher prices per hectare, due to the subdivision restriction making smaller parcels of farmland artificially scarce. South Africa is virtually the only liberal democracy in the world that restricts the subdivision of farmland.

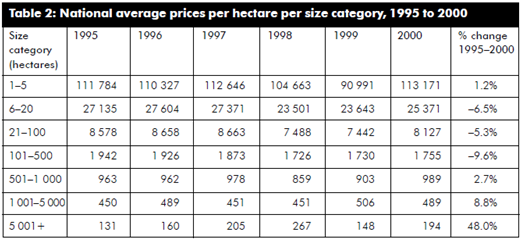

South Africa is land-rich. Therefore, land is cheap at an average price of a few thousand rand per hectare. Due to the subdivision restriction, cheap land availability is mostly restricted to large farms. As a result, small farms are selling for tens of multiples more per hectare than large farms. Even medium-sized farms of a few hundred hectares cost significantly more per hectare than large farms of thousands of hectares. These price differences are not due to scale as subdivision costs are relatively low. The price per hectare of smaller parcels of land will not be much more than that of large farms in a free land market. The table below from ‘Land reform and agrarian change in Southern Africa’ by Michael Aliber, Human Sciences Research Council and Reuben Mokoena, National Department of Agriculture, clearly shows the unnaturally large price differential between small, medium and large farms.

Due to the artificially higher prices per hectare of smaller farmland, access to farmland is restricted for lower and middle-income groups in South Africa.

Small and medium-sized farms are less competitive due to their artificially higher prices compared to large farms’ artificially lower prices. In the rest of the developing world, small farmers contribute a significant share of total farming production. The developed world, on the other hand, has fewer small farmers as these countries have fewer lower-income citizens that are interested in the hard work and relatively low income of small-scale farming.

South Africa has millions of poor citizens that would grab the opportunity to purchase a small area of farmland close to a town for a few thousand rand per hectare, but South Africa does not have a significant small farming sector. This is why so many poor South Africans pile into informal settlements instead of purchasing a smallholding where food could be cultivated and a permanent dwelling be built cheaply from mud and straw?

The Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act Repeal Bill was approved by Parliament in 1998 but the President never signed the notice. This meant that the Subdivision Act was never repealed. Initially, the government said it first had to improve the rezoning laws, however several rezoning laws were already in place to protect farmland from change in use. Even the repeal bill emphasised that sufficient rezoning laws were in place.

Years later, when the rezoning excuse lost all credibility, the government suddenly started with the old fallacy that subdivision restriction “protects” farmland from being subdivided into economically unviable sizes. But this is illogical. Market forces will deter farms from being subdivided into units too small for individuals to derive value from them. It will also determine a fair balance between small, medium and large farms based on the yields and value that people obtain from their farms.

An analogy of the situation created by the Subdivision Act would be if all new retail and commercial property development in South Africa were restricted to only large property spaces. This would result in small and medium-sized business owners competing for a dwindling supply of business spaces with a resulting hike in prices per square meter way above that of larger business owners. This would make it impossible for smaller businesses to compete with their larger counterparts. Imagine the justification of such an action being the supposed protection of business and the resulting failure of smaller businesses being used as a reason to keep enforcing the restriction.

The subdivision restriction is restricting equitable access to land and is clearly unconstitutional. If the subdivision restriction was challenged in the Constitutional Court, it would likely lead to the repeal of the restriction and the common law right to subdivide farm land will be in force once again. This would quickly free up the agricultural land market and make small farms available at a few thousand rands per hectare, greatly accelerating land reform, alleviating poverty and increasing food security for indigent South Africans. It will also show South Africans how land reform should be done, especially in light of the dangerous road of expropriation without compensation facing us.

The repeal of the subdivision restriction is supported by some of the leading land reform organisations in South Africa, and my non-profit organisation is being assisted by a leading Sandton law firm and advocate, on a pro bono basis, to take this matter to the Constitutional Court. It is moving slowly due to the few hours allocated to pro bono cases. I therefore plead with civil society and the farming community, who are staring down the barrel of expropriation without compensation, to take on the matter of challenging the constitutionality of the subdivision restriction in the Constitutional Court.

Roan Stoop is a statistician