Last week, the Fraser Institute, a Canadian think tank, confirmed what many of us already know - property rights in South Africa are in serious trouble. Of the 42 indices that the

Economic Freedom of the World report measures, South Africa's score has quickly declined in the area that is arguably the most important for a functioning and prosperous nation: the protection of property rights.

In 2018 (the most recent year data is available), the Fraser Institute found that out of 161 nations, South Africa now ranks 82nd in their strength of property rights protection. This represents a fall of 68 places compared to where South Africa sat just five years earlier, when the nation ranked a respectable 14th. South Africa's protection of private property rights now scores only marginally better than countries such as Russia and Egypt, and far below states such as Iraq, Brazil, and Kazakhstan.

Perhaps most worrying for South Africa is that this rapid decline in property rights began prior to the potential constitutional amendment to section 25 of the Constitution, which could allow for the expropriation of property without compensation. If enacted, this amendment would further undermine property rights in the rainbow nation.

Property rights are important for an immeasurable number of social and moral reasons, but one of their clearest benefits is their impact in boosting economic prosperity. Almost without exception, economies that have stronger property rights drastically outperform their counterparts with weaker property protections.

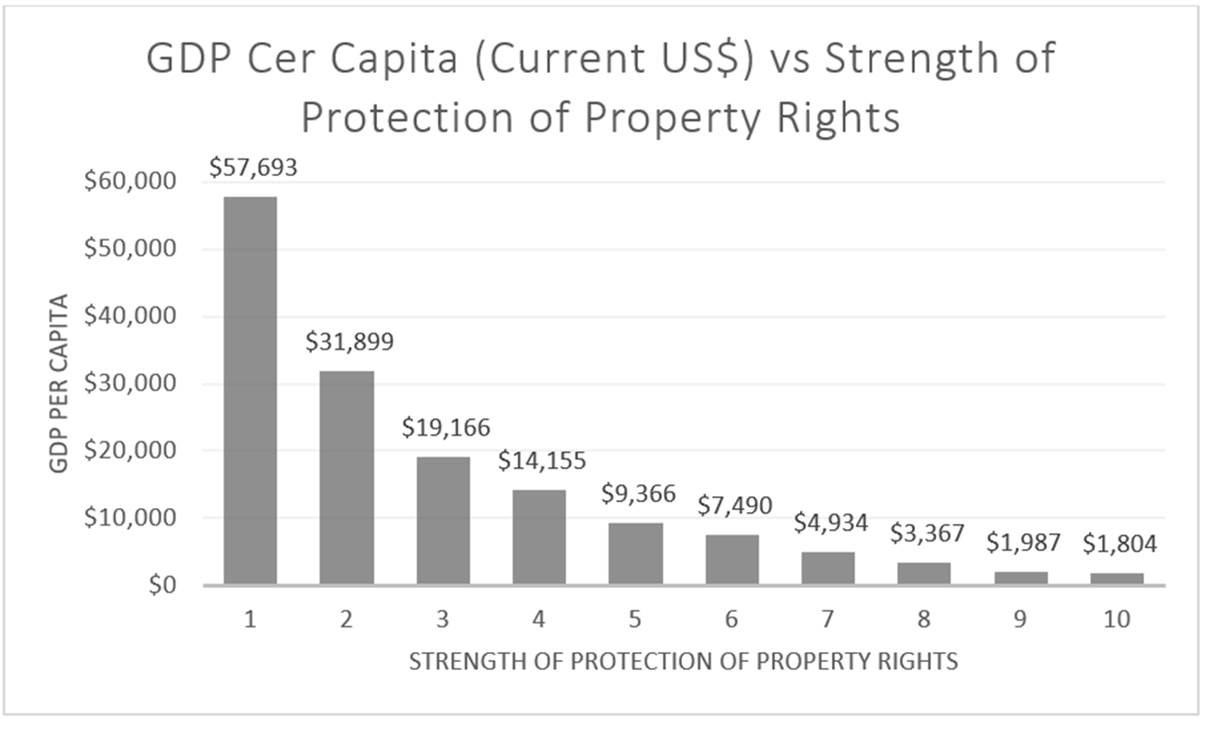

To highlight this phenomenon, I've taken the 161 nations that the Fraser Institute has data for and split them into deciles based on the strength of their protection of property rights. Decile '1' represents the 10 percent of nations with the strongest property rights, and decile '10' represents the 10 percent of nations with the weakest property protections. By finding the average GDP per capita (current US$) for each of these deciles, the importance of strong property rights becomes evident.

*GDP per capita data is taken from the WorldBank using 2018 data; the most recent year the Fraser Institute has data.

Nations in the decile with the strongest property rights have an enormous average GDP per capita of close to $60,000, which equates to 3098 percent more than the decile with the weakest property rights. In the 6th decile - where South Africa currently sits - average incomes are staggering 7.7 times lower than the average in the strongest decile.

While several ingredients such as low regulation, freedom to trade, sound money, and government size are crucially important in the recipe for economic prosperity, many of these components remain contingent on having strong property rights.

Take freedom to trade as an example.

Many consider reducing tariffs and opening up domestic markets to the global economy as a panacea for economic growth. Indeed, in many ways, it is. However, without substantive property rights underpinning a society, citizens lack the certainty that the fruits of their labour will be protected and the incentive to invest, innovate or actually produce anything to trade vanishes.

Similarly, achieving any sort of sound money or sustainable rate of inflation in the absence of property rights is equally unrealistic, given that the result of less investment, which is a consequence of weak property rights, is a depreciated currency and a higher rate of inflation. And as seen in Zimbabwe, if this is coupled with government printing more money, the results are

disastrous.

Given the importance of strong property rights, it is perhaps unsurprising that between 2013-2018 (the period in which South Africa's protection of property rights slipped from the strongest decile to the 6th), average per capita GDP dropped over 6.7 percent, or roughly $500.

Unfortunately for South Africa, since 2018, the economy has only worsened. Even before the policy response to COVID-19 decimated the rainbow nation's GDP, resulting in an annualised

contraction of 51%, South Africa was already in its

second recession in as many years and experiencing it's the longest downward economic cycle

since 1945. The

Centre for Development and Enterprise has predicted youth unemployment could now be upwards of 70 percent - up from an already celestial high of

56 percent in 2019.

Some economists are optimistic that by 2023-24, economic activity will have returned to the less-miserable pre-lockdown level. However, suppose the African National Congress (ANC) is successful in their goal of amending section 25 of the Constitution so that when the state takes private property, zero compensation could also bizarrely count as "just and equitable." In that case, any suggestion of substantive economic recovery is senseless.

As Dr Tom Palmer, Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, has recently

highlighted: Whether it be Kazakhstan in the 1920s, Ukraine in the 1930s, China in the 1950s and 1960s, or Venezuela in the early 2000s, the result of expropriation without compensation (EWC) remains timeless and cruelly predictable. There is always food shortages, hunger, mass migration, and countless deaths.

To revitalise the flailing economy, the ANC should reject the constitutional amendment pertaining to EWC and announce a renewed commitment to upholding private property rights. Regrettably, given President Ramaphosa’s commitment to the economically illiterate policy of EWC, this scenario seems unlikely.

If EWC is enacted, South Africa's already weak property rights will be decimated even further, and so too will any hope of an economically prosperous future. As I've noted before, South Africans need only

look north to Zimbabwe to see the catastrophic consequences of this kind of policy.

Alexander C. R. Hammond is a Policy Advisor at Institute of Economic Affairs and a Senior Fellow at African Liberty. With thanks to Isabella Crane, Intern at the Institute of Economic Affairs.

This article was first published on City Press on 17 September 2020