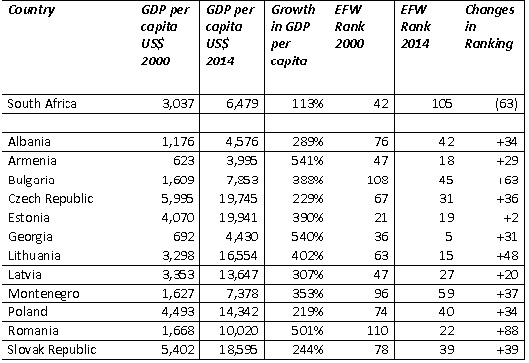

In 2000, South Africa (SA) was listed as the 42nd most economically free country in the world. That same edition of the Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) report listed Bulgaria, a former communist country, at 108th (66 places lower on the rankings). Fourteen years later, in 2014, the positions were reversed. Bulgaria had shot up the rankings to 45th place and SA had plunged down to 105th (60 places lower than Bulgaria).

The gains in GDP per capita of Bulgaria and other former communist/socialist countries that have opted for greater economic freedom are striking. Without fail, they have outperformed countries like SA that are sliding down the rankings. It is time for SA to take note and change direction.

Effects of loss of economic freedom

The loss of economic freedom reflected in SA’s plunging ranking tells us why our country is in recession, why unemployment measured by the expanded definition totals 9.3 million people (36.4% of the potential workforce), why the economies of other countries such as Bulgaria, with an unemployment rate of 9.8%, are doing so much better than ours in the difficult economic conditions that currently prevail worldwide.

The direction of change in the economic freedom ratings and rankings have consequences. The EFW analyses, which have been carried out annually for more than two decades, show conclusively that increased economic freedom leads to higher economic growth, higher incomes per capita, higher incomes for the poorest people in the country, higher life expectancy and greater political and civil rights. The changes in economic freedom rankings show that, since 2000, SA citizens have lost some of their freedoms, while citizens of Bulgaria and many other former Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries have gained.

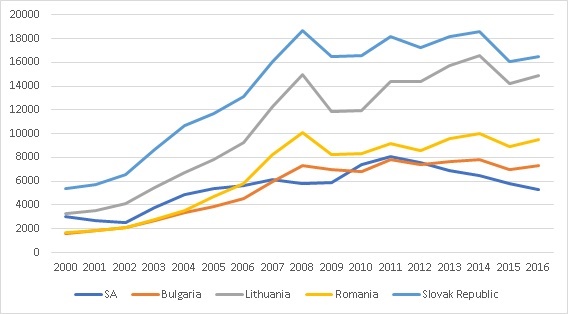

It really matters that SA’s EFW ranking has declined so badly while Bulgaria’s has improved by a similar number. A simple test will indicate to us how much it matters. The World Bank reported that in 2000 SA’s GDP per capita (current US dollars) was US$3,037, Bulgaria’s US$1,609. In 2014, SA’s was US$ 6,480, Bulgaria’s US$7,853. SA’s GDP per capita increased by a mere 113 per cent in the 14 years compared to Bulgaria’s 388 per cent. Consider how much better off the average SA citizen would have been if their incomes had averaged the same as Bulgaria’s or those of other former communist/socialist countries that opted for greater economic freedom.

Bulgaria’s gain in economic freedom

Bulgaria gained in the ratings by selling government enterprises and investment by public auction, which reduced governments’ role in the economy and boosted the share of the private sector. It drastically reduced the inflation rate by reigning in the rate of money growth, removed restrictions on the freedom to own foreign currency bank accounts, and significantly reduced the tax rates. Government enterprises and investment as a share of the economy declined from 38.95% (2000) to 15.41% (2014), having been 98.40% in 1990 under communist/socialist rule. Inflation declined in the same 14 years from 10.32% to minus 1.42% and the annual money growth from 76.68% to 9.34%. The top marginal tax rate was cut from 38% to 10% (individuals and companies) and the top marginal and payroll tax from 56% to 34%.

Increased economic freedom will give SA high-growth radical economic transformation

SA needs to free up the economy to achieve the high growth rate essential for increasing incomes and reducing poverty rather than pursuing policies based on ideologies that former communist/socialist countries have already learnt first-hand create poverty and misery.

SA’s rapid decline in the EFW rankings and sluggish per capita GDP growth was caused by a substantial increase in government’s share of the economy, from 17.80% of the economy in 2000 to 36.34% in 2014, crowding out the private sector in the process. There was a slight reduction in the marginal and payroll tax rate but, at 41%, the tax rate remains high by international standards. Foreign exchange controls, which hamper trade and investment, remain in place, and there has been a large increase in regulatory trade barriers and compliance costs for importing and exporting, a substantial increase in bureaucracy costs (red tape), and an escalation in the payment of bribes.

South Africa’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have become millstones around the economy’s neck and are weighing it down. Instead of contributing to wealth and job creation, they consume taxpayer resources and provide powerful evidence as to why government officials (even in the absence of corruption) cannot be expected to run businesses efficiently. One reason is that decision-making is political and not strictly business oriented. Another is that in most cases SOEs are monopolies, protected from the discipline of competition from alternative providers by prohibitions that prevent alternative providers from competing with them. Where private firms are compelled to function efficiently or else lose business, get taken over, or go bankrupt, SOEs are shielded from those very economic forces that would compel them to function more efficiently.

Former communist/socialist countries are opting for economic freedom

The 21st Century has seen a rapid change in the policies followed by former Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries. The majority have moved away from the policies they were forced to follow in the past towards greater individual and economic freedoms. The direction of change has had a significant effect on their economic outcomes. A change in the direction of greater economic freedom results in higher economic growth – a worsening economic freedom score inevitably leads to economic decline.

Table: Growth in GDP per capita and changes in EFW rankings 2000-2014 (SA and former Soviet and Eastern Bloc Countries)

Source: World Bank (current US$) and EFW 2016 – compiled by EG Davie

Graph: Growth in GDP per capita (2000 to 2016)

The people and governments of the countries listed in the above Table that have climbed up the economic freedom ladder are to be congratulated. Their countries rank in the top 37% of the most economically free countries in the world, a position that SA was in at the turn of the century. Some of them have performed spectacularly from adopting sensible economic policies. The 2017 edition of Economic Freedom of the World is to be released later this month. We will then discover whether the listed countries have continued to progress and if there has been a positive turn-around in SA’s ratings and freedom ranking.

Author Eustace Davie is a director of the Free Market Foundation. This article may be republished without prior consent but with acknowledgement to the author. The views expressed in the article are the author’s and are not necessarily shared by the members of the Free Market Foundation.