Media release

29 June 2017

Release immediate

Sir Ketumile Masire, Nelson Mandela and the Free Market Foundation

Ketumile Masire (2001): “This is the time to demonstrate to the world that, as fellow Africans, we are capable of working together so that we can all enjoy peace, freedom and dignity.”

FMF was saddened to hear of the death last week of statesman Sir Ketumile Masire, president of Botswana from 1980 to 1998. Masire is widely credited with transforming Botswana’s economy, and promoting democracy and inclusivity.

Sir Ketumile Masire was the recipient of the FMF’s 2000 Free Market Award for his “exceptional contribution to the cause of economic freedom”, presented in April 2001 at an event attended by Nelson Mandela.

Michael O’Dowd, then-FMF chairman, presenting the award, said: “Some people may think it strange that a free market organisation should be honouring somebody for his acts as the head of a government, but this is not so. It is true, unfortunately, that free market organisations spend a lot of time criticising the actions of governments but they are not opposed to governments as such. On the contrary, we fully realise that free markets can only exist under the aegis of a good government.”

In accepting the award, Masire said: “One of the key initiatives that I took before leaving office was to put in place the process of charting a long-term vision for Botswana.” Critical elements of Masire’s vision included: “…an educated and informed nation; a prosperous, productive and innovative nation; an open, democratic and accountable nation; a moral and tolerant nation…” He added: “This is critical for fostering an environment in which free and uninterrupted economic activity can take place.”

O’Dowd: “Over 35 years, Botswana has had the highest rate of economic growth in Africa ... Botswana has proved that there is nothing about Africa, neither in the character of its people, nor in its traditions, nor in its history, that closes to them the prospect of joining the first world.”

Masire pointed out that an important factor that contributed to Botswana’s sustained economic growth was an “unflinching commitment to public sector reform” He added: “There is indisputable evidence that … the absence of bureaucracy in the public sector enhances private sector development.”

“Standard international comparisons show Botswana as being the freest economy on the continent of Africa”, noted O’Dowd. “What then did Botswana do right? Botswana maintained all the institutions and practices which constitute a free market economy. It consistently protected and respected property rights and nationalised nothing. This is crucial. It upheld a proper system of law under which contracts are dependably enforceable. It refrained from interfering with the day to day operation of the economy by means of controls and it refrained from setting up grandiose state enterprises as the old South African government did. This has been the road to success followed by every successful economy in the twentieth century, and it was the road followed by Botswana.”

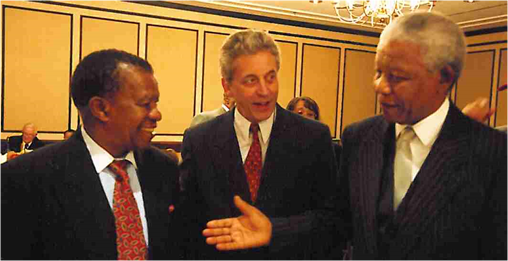

Sir Ketumile Masire, Leon Louw and Nelson Mandela

Note to the editor: Full speeches below

Michael O’Dowd’s full speech can be read here:

Sir Ketumile became President of Botswana in 1980 and retired in 1998, and that means he was President for 18 of the Republic’s 35 years of existence.

The award honours, of course, the remarkable, indeed extraordinary, achievements of Botswana, which I shall describe in more detail in a moment. To this achievement, Sir Ketumile, as President, and before that, as vice-President made an enormous personal contribution, but it was nevertheless the achievements of the whole country and all its people; and so today we are honouring Sir Ketumile Masire in two capacities. We are honouring him personally for his personal contribution, but we are also treating him as the symbolic representative of the Botswana people as a whole, and through him we are honouring them all.

Some people may think it strange that a free market organisation should be honouring somebody for his acts as the head of a government, but this is not so. It is true, unfortunately, that free market organisations spend a lot of time criticising the actions of governments but they are not opposed to governments as such. On the contrary, we fully realise that free markets can only exist under the aegis of a good government. Many of the greatest heroes of the free market have been statesmen like Sir Robert Peel in England in the 19th century and Lee Kwan Yu in Singapore in the twentieth, and credit for the achievements of the successful economies of the world is quite rightly given primarily to their governments.

What then has Botswana done which is so remarkable? In the 35 years since independence, Botswana has an impeccable record of democracy, as good as anything in the world, including the first world. Such a record is extremely rare, not only in Africa, but equally in Asia, and for that matter, in South America.

Secondly, over 35 years, Botswana has had the highest rate of economic growth in Africa, and has been one of the high growth economies in the world, in the same league as such admired economies as Singapore. It has come from being one of the poorest countries in the world, to being one of the richest in Africa, in the same league with the Republic of South Africa (which took much longer to get there hindered as it was by apartheid). If Botswana can sustain something like the same rate of growth for another 30 years, it will by then, in the lifetime of many who are already mature adults, be a fully-fledged member of the first world. Botswana has proved that there is nothing about Africa, neither in the character of its people, nor in its traditions, nor in its history, that closes to them the prospect of joining the first world.

Finally, and in our opinion, this is the case of the second achievement, and a major contributor to the first, Botswana has, consistently over 35 years, maintained a basically free market based economy. The standard international comparisons show Botswana as being the freest economy on the continent of Africa. For many years, it towered above all the others. Recently, its lead has been narrowed not because it has gone backwards, but because many other countries in Africa (including, of course, our Republic of South Africa) have made big improvements, but still at today’s date, it is the freest economy in Africa and the fastest growing, and one of the most democratic.

Those who wish to disparage Botswana’s achievement will say that it was ‘merely’ the result of an economic windfall – the discovery of diamonds. There was such a windfall, but recent history shows that it is extremely rare for a mineral windfall to become the base on which sustained economic growth is built. In the second half of the twentieth century it was conspicuously resource-poor countries like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore that did well economically.

So much was this so that some economists have seriously suggested that mineral wealth is a curse as it certainly can be. It would seem, from the historical record, that it is at least as difficult to administer an economic windfall successfully as to bring on a resources poor economy. Both things are possible – both have been done, but what Botswana did successfully seems to be the more difficult of the two.

What then did Botswana do right? In the first place, they acknowledged that in order to develop their mineral resources they needed international expertise. At a time when other countries (like Zambia) were spending their own desperately scarce resources to drive foreign capital out of their countries, Botswana brought it in. They recognised that

De Beers’ achievement in stabilising their diamond prices was vital to their interests as diamond producers and they whole-heartedly co-operated with it. They made contracts with foreign investors which stuck.

Then they did not use the revenue, which they received from the mines either to build palaces, or to buy armaments, nor did they channel it into Swiss bank accounts (Botswana has been identified as the least corrupt country in Africa). They used it first to create an excellent but not extravagant education and health system. Then they used it to keep the rest of their taxes low. Low taxes have been a hallmark of most successful economies.

Then they did not allow the creation of a hot house of protected and subsidised industries, paying wages out of all proportion to what the bulk of the population can hope to earn, thereby creating a vested interest which would prevent the development of internationally competitive industries. This is perhaps the cul-de-sac into which countries that experience a mineral–based windfall most usually go. It leads to an economy entirely dependent on the primary producer, with a parasitic secondary sector. When the mineral producer comes to the end of its life, as all mineral producers, in their nature, must do, the secondary sector collapses as well.

In Botswana, on the contrary, we see at the present time, a much-improved rate of growth in the manufacturing sector as the mining sector begins to decline. One reason for this is that while Botswana has always (since independence), had proper free and democratic trade unions, the unions have never been allowed to exercise undue or disproportionate influence on government policy, as has happened in many places, not only in Africa, but in Europe as well, with dire consequences for economic growth.

Most important of all, as I have already said, throughout the period, Botswana maintained all the institutions and practices which constitute a free market economy. It consistently protected and respected property rights and nationalised nothing. This is crucial. It upheld a proper system of law under which contracts are dependably enforceable. It refrained from interfering with the day to day operation of the economy by means of controls and it refrained from setting up grandiose state enterprises as the old South African government did. This has been the road to success followed by every successful economy in the Twentieth Century, and it was the road followed by Botswana.

So Botswana got it right. Botswana is Africa’s success story, and if we are serious about an African Renaissance, African success stories are what we have to find, to acknowledge and honour.

I have the greatest pleasure and I am deeply honoured to be able to present to Sir Ketumile Masire both in his personal capacity and regarding him for the moment as the symbolic representative of the Botswana feat – the Free Market Award 2000.

Sir Ketumile Masire’s full speech can be read here:

ADDRESS BY SIR KETUMILE MASIRE FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA ON THE OCCASION OF ACCEPTANCE OF AWARD FROM THE FREE MARKET FOUNDATION

4 APRIL, 2001

Mr Chairman, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen:

It is a great honour for me to receive this award from the Free Market Foundation, an institution renowned for promoting socio-economic development and for fostering free market enterprise in developing economies. I am grateful for their recognition of the achievements of my country during my tenure of office. But I must hasten to mention that, there are a number of other personalities without whom our enduring efforts would not have deserved such recognition.

I would like, from the outset, to express my gratitude to Mr Michael O 'Dowd for his kind words – not only those directed to me, but those about my country, Botswana as well. For this, I am most grateful.

We live in an era during which we have to deal with the harsh realities of globalisation. The creation of a borderless world. A global village presents us with many challenges, indeed. There are as many opportunities that need to be carefully exploited, as there are challenges.

Under such circumstances, it was most appropriate for us in Botswana to take stock of our accomplishments and failures over the decades since we attained independence.

As you will no doubt be aware, I retired from public office two years ago. But before I stepped aside, I handed power over to an individual whom I believe will carry Botswana to even greater heights. I believe he will continue to address with vigour the development challenges facing Botswana in the new millennium.

I retired from public office after serving my country for many years in various capacities. I therefore had the opportunity to contribute towards the political and economic advancement of Botswana.

One of the key initiatives that I took before leaving office was to put in place the process of charting a long-term vision for Botswana. This Vision came about after a series of consultations with the people of Botswana. I have no doubt that it reflects a wide spectrum of the aspirations of the people of Botswana.

The long-term Vision for Botswana identifies seven major goals that should be attained by the year 2016. The Vision will ensure that – through education and development of human capital – future generations of Batswana can achieve a reasonable level of literacy, and that the country can boast of a pool of well-trained manpower.

The critical elements of our vision provide for creating:

• an educated and informed nation;

• a prosperous, productive and innovative nation;

• a compassionate, just and caring nation;

• a safe and secure nation;

• an open, democratic and accountable nation;

• a moral and tolerant nation, and

• a united and proud nation.

This is the central challenge for many of the developing economies. The underlying principle of our Vision is the preservation of the positive aspects of our cultural heritage. This is critical for fostering an environment in which free and uninterrupted economic activity can take place.

In keeping with the traditional values of Batswana, and consistent with our national development planning objective of social justice. we recognise that every Motswana is entitled to have access to economic opportunities in his own country.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

When we sought independence thirty-five years ago, our critics were very vocal. They derided us for being irresponsible in seeking political independence when we could hardly feed ourselves. At the time, we could barely balance our budget without external support.

Furthermore, for some time after independence, there was very little accumulation of private savings in the society. What little capital existed was largely in the form of cattle – and the scourge of the drought dealt the livestock industry a severe blow from time to time. Nonetheless, we persevered.

To date, Botswana has recorded a very high rate of savings at the macro level. The earnings – most of which have accumulated in the public sector – are largely generated from the mineral sector.

In order for the rest of the population to derive benefits from these fortunes, we have had to reinvest them in the economy through development, financial and investment organisations, as well as education. Indeed, we are grateful to South Africa for admitting our students to their institutes of learning.

This we have done successfully – thanks to prudent economic management. We have been able to support a high rate of economic growth. In order to derive even more benefits from the revenues generated over time, we are now finalising the process of establishing Botswana as a regional financial centre to serve the Southern African region.

There is an equally important factor – yet less recognised – that has also contributed to our sustained economic growth. This is our unflinching commitment to public sector reform.

There is indisputable evidence that, in the new economic order, the absence of bureaucracy in the public sector enhances private sector development.

Therefore, one of the efforts of government in the recent past was to prepare for the challenges of participating in and benefiting from-the global economy. We have thus reduced the degree of government involvement in those activities that can best be performed by the private sector, including the public enterprises.

At the same time, we have steadfastly adhered to the principles of openness transparency, good governance, and promotion and development of the private sector.

An equally important development was government's undertaking to review the size and structure of the public sector.

The privatisation of certain activities performed by the government is one of the consequences of reforms undertaken. This is also a concrete manifestation of the government's promotion of the private sector.

I must emphasise that many other factors have contributed to the successful socio-economic transformation of Botswana over the years, in addition to good fortunes and prudent economic management. A long and enduring democratic tradition of Batswana has also sustained us.

We have also aspired to a high level of political maturity in avoiding adversarial partisan relations. We encourage free and well-informed debate. Our political parties have a responsibility to distinguish between partisan political interests and issues of national concern.

Botswana has also thrived as a result of the successful partnerships it forged, both in the region and internationally. We are a country with a small population. We therefore suffer the constraints of a small domestic market. Consequently, Botswana has had to look for markets for its products and services beyond its political boundaries.

In this context, the Southern African Customs Union (SACU)- in which Botswana enjoys free trade with other member countries – has been an important factor in Botswana's economic development.

Beyond the SACU, in partnership with other countries in the region, Botswana has been instrumental in nurturing the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Both SACU and SADC provide the basis for the creation of an important economic and political alliance of the Southern African countries.

For many tangible benefits to be derived therefrom, such an alliance needs to be well managed. It has the potential to increase opportunities for regional prosperity, peace and harmony.

We should recognise the value of regional co-operation as one of the essential prerequisites for the attainment of the ideals of the African Renaissance.

Unfortunately, there seem to be many obstacles that thwart the completion of this great enterprise. We need to overcome this challenge. We must be united in our endeavour to transform our society into A GOOD SOCIETY – A JUST SOCIETY.

Together we must develop the mechanisms for settling our differences through dialogue rather than war.

Together we must seek to prevent the outbreak of violent conflicts by establishing institutions through which people can exercise the right to determine how they are governed.

We must be UNITED in finding ways to prevent the spread of diseases such as HIV/AIDS – diseases that inflict so much pain and misery – that erode the very fabric of society and perpetuate a cycle of poverty.

Without UNITY, we cannot hope to enjoy the fruits of our freedom. The architects of our independence have fought- and died for our freedom.

This is the time to demonstrate to the world that, as fellow Africans, we are capable of working together so that we can all enjoy PEACE, FREEDOM and DIGNITY.