The parliamentary ad hoc committee on amending the Constitution to provide for expropriation without compensation said it intended to speed up the process and settle the matter by the time of the May 8 general election.

With Parliament now dissolved, we know their sped-up endeavour will not come to pass.

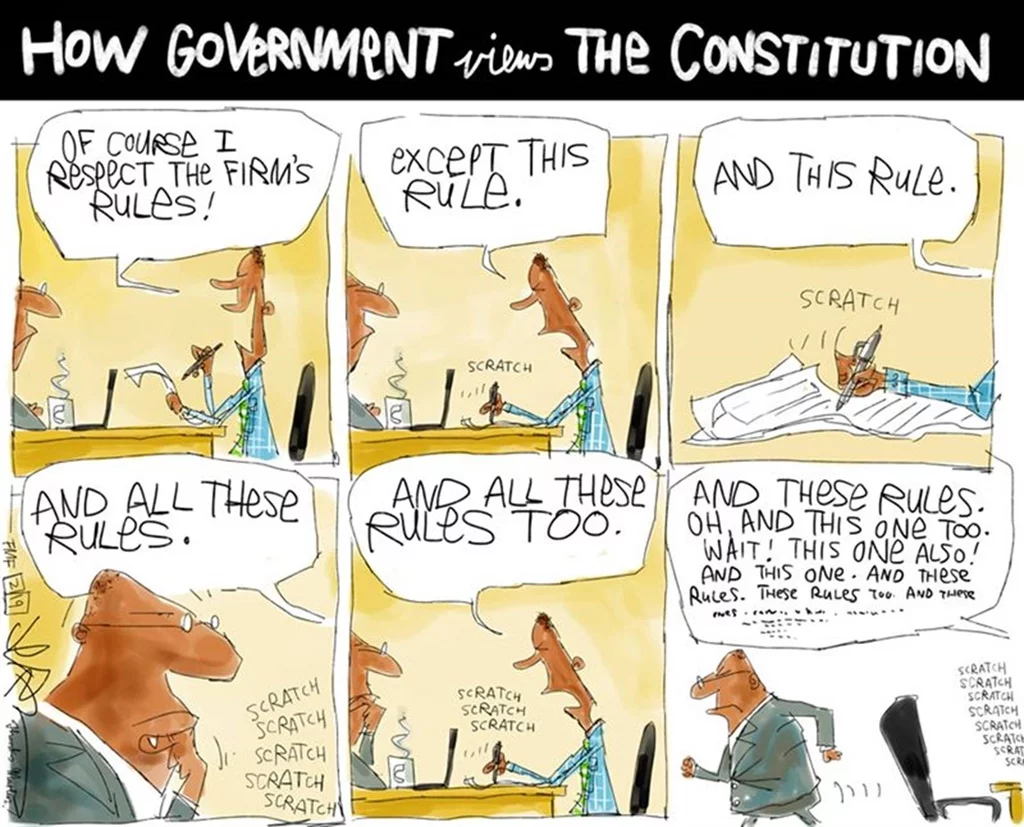

But those statements indicated a contempt for the rule of law and the imperative of participatory democracy that characterises our constitutional order.

Rushing a constitutional amendment would be a procedural irregularity that could have the amendment set aside in court, but it also a philosophical assault on the basic structure of the Constitution.

In 1961, in his book The Foundations of Freedom, eminent constitutional law professor and anti-apartheid activist Denis Victor Cowen said that simply having a supreme Constitution is not a sufficient condition for having a free society based on the types of values today encapsulated in section 1 of the Constitution.

He indicated that it takes a culture of respect for the institutions, protections and values that the Constitution seeks to advance and entrench for the principles of the Constitution to truly be respected and lived.

Without this culture, a Constitution is nothing but an empty document that will be circumvented, if not totally ignored, by those expected to enforce and obey it.

Unfortunately, we see this happening today.

The decision by Parliament to press ahead with amending section 25 of the Constitution to remove or otherwise weaken the right to receive compensation when one’s property is expropriated, was itself already a clear indication that the government has some level of disrespect for the protections the Constitution affords.

It has been noted repeatedly in the public discourse that the Constitution already contains generous provisions for fast-tracking land reform, a fact government has acknowledged.

Despite this, Parliament intends to still bring about substantive change to the most important law in South Africa. Amending a law for amending’s own sake is an abuse of proper, established process and a betrayal of constitutionalism.

To think that the amendment would have been finalised before May 8, which is only about three months away, is constitutionally deplorable.

It is deplorable because the committee still needs to produce the Constitution Eighteenth Amendment Bill to change section 25, which must be subjected to a public participation process in addition to the process already had in 2018.

Last year’s process was to receive the public’s views on the parliamentary resolution – the public still need to review the actual text and implications of the amendment itself.

But the public participation exercise has hereinto been tepid.

The hearings roadshow was characterised by anti-constitutionalist factions bussing in their supporters to repeat their talking points and shout down anyone who dared disagree.

Members of the review committee picked and chose who got to speak, tailoring the whole process to align with their forebegotten conclusions.

The majority of written submissions to Parliament were firmly against amending the Constitution.

This did not deter the committee, however, because it disregarded most submissions and only considered a “sample” – adding to the fallaciously enforced message that most South Africans want their rights to be weakened.

Indeed, the government has received no mandate to pursue expropriation without compensation.

A mandate can only be lawfully obtained if the facts of the case are supplied dispassionately and objectively.

In other words, there must be no material misrepresentation of the details of the mandate.

But when anti-constitutionalist factions engage their supporters, they present the phenomenon as a process whereby agricultural land will be taken from the rich and given to the poor.

This is not what the amendment to the Constitution will do.

The amendment will be a law of general application – it will not discriminate between white and black or rich and poor.

It will give the government a general power to expropriate property for nil compensation under certain conditions. This power can, and will, be wielded against anyone.

In other words, everyone’s property rights will be diluted by this amendment.

Only if government asks the people “do you want to allow the government to seize your things without paying you for it?” might it receive a mandate.

But it knows virtually no South African is going to agree to this legalisation of theft.

It is not enough for the government to follow the procedure in section 74 of the Constitution to bring about an amendment.

It must also demonstrate a respect for constitutionalism, otherwise it risks embarking on a process of delegitimising the Constitution itself in the eyes of the world, and in particular, in the eyes of ordinary South Africans.

To demonstrate such a commitment, any process to amend the Constitution must be played out in an intellectually honest fashion, so that a true national consensus can be built around the idea.

Whatever the case, giving South Africans only three months – if that – to study, internalise, and comment meaningfully on a proposed amendment to the Constitution is woefully inadequate and insulting to the very idea of participatory democracy.

Even if this process starts after the election drama has subsided, Parliament must give citizens a generous amount of time to engage.

• Van Staden is legal researcher at the Free Market Foundation and is pursuing a master of laws degree at the University of Pretoria. He is author of The Constitution and the Rule of Law (2019)

This article was first published in City Press on 1 March 2019