The state of South Africa’s basic education is a topic of constant debate – by political parties, the media, civil organisations and the general public. Even though basic education has had a positive impact on South Africa’s development post-apartheid, problems such as dismal educational outcomes and the absence of teachers torment us, and, especially, low-income families.

These problems aside, some progress has been made in addressing and eradicating the legacy of apartheid in education. Increased access to education has accelerated the growth of the black middle class so that, for the first time, in 2008, the size of the black middle class surpassed that of whites.

Throughout human history, education has been a big factor in the development of nations, and, therefore, South Africa’s prosperity is dependent on the quality of its basic education.

Even though South Africa’s education faces many challenges, it is fair to say that, on balance, the opening up of educational opportunities has had a positive impact on our society.

South Africa’s basic education challenges

Even with the progress that has been made since 1994, relative to the past, South Africa’s basic education is not doing as well as in other countries. Government is failing in many respects to pursue the reforms needed to improve the country’s education.

Besides the absence of teachers and dismal outcomes, other problems that challenge the provision of education in South Africa range from the shortage of educational facilities, to overcrowded classrooms, and the destructive actions embarked upon by teacher unions like SADTU (South African Democratic Teachers Union).

Most affected by government’s failure to improve public basic education are children from low income families – where parents cannot afford to seek out alternative sources of education for their children.

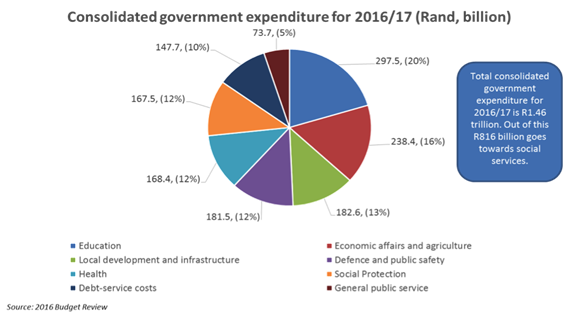

Twenty per cent of South Africa’s government expenditure–the biggest allocation compared to other sectors, as shown on the 2016 Budget Review above – goes to education. Yet the outcomes still disappoint.

“According to Africa Check, South Africa ranks behind poorer African countries like Kenya, Swaziland, Tanzania and Zimbabwe on literacy and numeracy. That we are behind these poorer countries with all our privileges ought to unsettle us all.”

In Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), results released in 2016, South Africa ranked second last in the world. African countries like Botswana, Egypt and Morocco, performed better than South Africa.

Could independent schools be the solution to South Africa’s education problems?

As government fails to produce desirable results on public education, reforms are urgently needed to make improvements. Government needs to look into encouraging and creating an environment where independent schools can thrive and grow.

Independent schools are already having a significant impact on South Africa’s education. Between 2000 and 2010, according to an article that appeared in The Economist in December 2015, the number of government schools established in South Africa fell by 9%; while that of independent schools grew by 44%.

But parents from low income families cannot afford many of the independent schools. Private education is expensive. Government needs to find ways to encourage the establishment of low-fee independent schools to fuel not only competition between private schools, but also competition between low-fee private schools and public schools, and so improve overall basic education in South Africa.

Low-fee private schools have a huge potential. The Spark school in the suburb of Bramley, is a good example of the kind of education system the government could pursue.

“Quality independent schooling such as Spark, priced at R19,100 a year, means families with widely different incomes can afford to, or simply choose to, send their children to low-fee schools,” Lisa Steyn wrote in the Mail & Guardian in December 2016.

Schools like Spark are badly needed, and the task for government must be to encourage the growth of such low-fee schools so that education becomes competitive and its quality improved.

Competition would improve not only private education, but also public schools, because public schools would have to compete with other schools by providing quality education for South Africa’s youth.

The role played by businesses, parents, and communities in general, is critical in any effort to improve the education sector in this country. These stakeholders, other than our bureaucratic government, must assume greater control of the schools in their communities. The participation of the private sector in our schools would demand greater commitment from all involved.

Dr. Thomas Sowell, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, once said that there are no solutions in economics, there are only trade-offs. Competition will not be the solution to South Africa’s education problem – but it could be government’s first step towards bringing about significant reforms in the sector.

Phumlani M. Majozi is a youth co-ordinator and non-executive director at the Free Market Foundation

This article was first published in The Gremlin on 29 August 2017 and in Business Day on 30 August 2017